by Ken Longfield and Ken Hulme

We know, that like Don Quixote, we are tilting at windmills with this little essay. Many in our Appalachian (mountain, etc.) dulcimer community use the term scheitholt to describe an elongated box over which passes any number of strings from five to fifteen. We even used the term until we started investigating it. So, let us examine this word and instrument to discover why it should not be applied to instruments found in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, Ohio, etc.

The term Scheitholt traces back to a single source, the Syntagma Musicum (Volume two) of Michael Praetorius 1 The first volume of the Syntagma Musicum discusses both the sacred and secular music of the period. The second volume, the one which is of interest to this essay, concerns musical instruments. The third volume begins with a list of musical terms and their meaning and goes on to discuss notation and how to practice.

Volume Two: De Organographia is a study by Praetorius of musical instruments of his day. The primary focus is the organ. In the first part Praetorius discusses how to classify musical instruments. Part 2 contains classifications of the instruments of his time and contains the notable woodcuts of those instruments. Parts 3 and 4 are about the organ while Part 5 presents specifications of noted organs of the time.

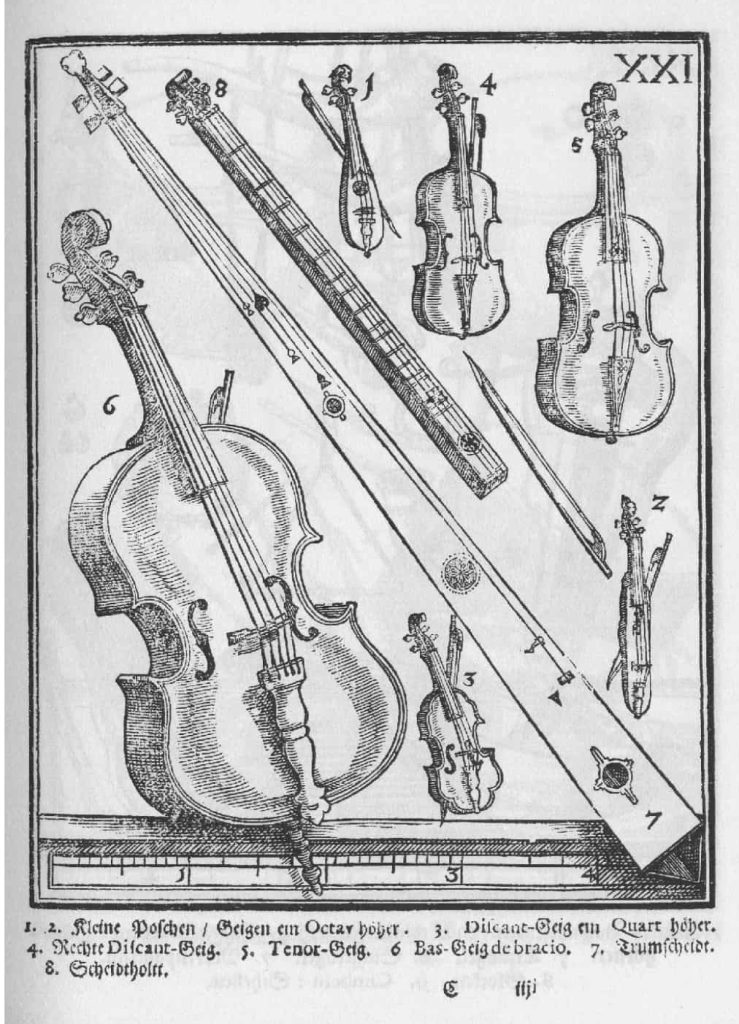

This woodcut (plate 21) of De Organographia is where Praetorius illustrates what he calls a scheitholt. It is number 8.

In the text which accompanies this illustration Praetorius describes the scheitholt as being made from three to four pieces of thin wood and having three to four strings and tuning pins. The entire discussion of the scheitholt is a short paragraph of 168 words. 2 He begins by calling the instrument “a piece of junk” from a musicians point of view. 3

In German, scheit means log or piece of wood, while adding holt or holz means firewood. He continues by describing the strings as being made of brass and goes on to give two tunings: one where the strings are tuned in unison and the other where one string is tuned a fifth higher than the other strings. 4

In explaining how the instrument is played, Praetorius says that the thumb strums the strings while a small, flat wood stick is used to press down the strings at the frets which are made of brass.

From this we learn that a scheitholt has, at most, four strings of brass and brass frets.

Wilfried Ulrich, in his book The Story of the Hummel, also discusses the scheitholt. He tackles Praetorius’ description of the scheitholt and notes an important feature, namely, a small hook at the fourth fret. This hook, which is on the second string in from the player’s side of the instrument, allows the string to be raised to a fifth tone above the first string. 5 We have never seen this on any instrument purported to be a scheitholt.

So, how did we come to apply the term scheitholt to the zithers found among the Pennsylvania Germans of Berks and Lancaster counties? Henry Mercer in his address to the Bucks County Historical Society on January 20,1923 in Doylestown, Pennsylvania did not use the term. Rather he called them zithers. I guess we can’t 6 place the blame on Mercer.

Musicologist Charles Seeger writing in The Journal of American Folklore notes the connection of the Appalachian dulcimer with instruments from northern Europe, “the Icelandic langspil, Norwegian langeleik, Swedish hummel, Danish humle, Lowland Noordsche balk, German Scheidholt, and French and Belgian buche or epinette des Vosges.” 7

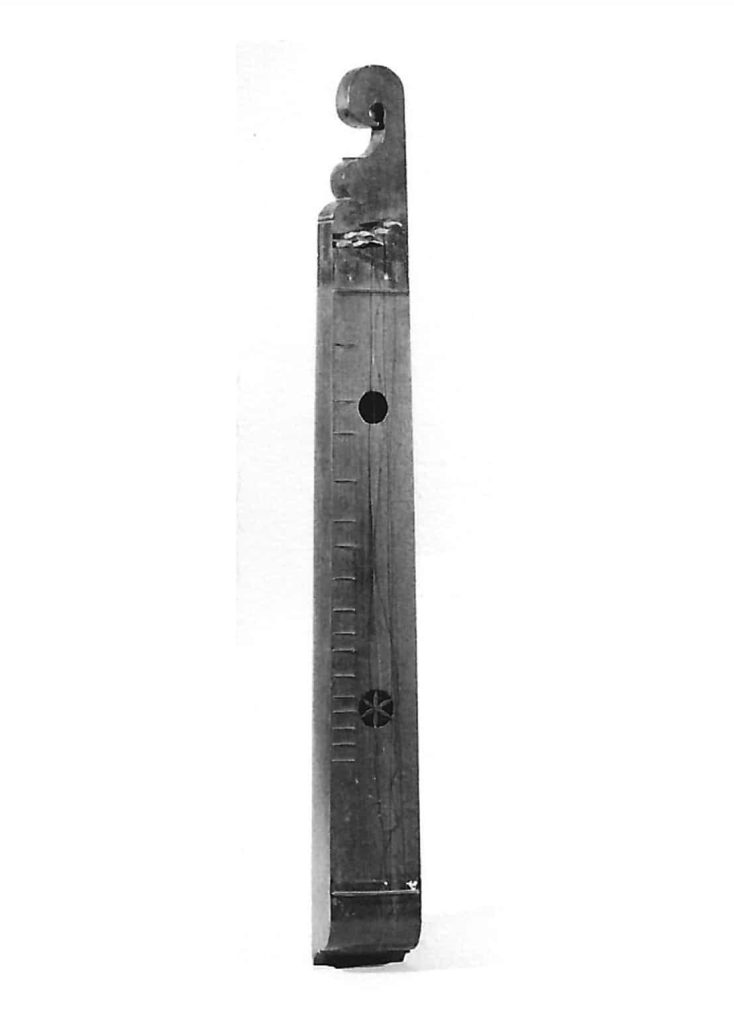

Among the instruments of the Crosby-Brown collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is this one:

Among the instruments of the Crosby-Brown collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is this one:

Currently it is identified as a “Zither, European, late 18th - mid-19th century.” However, Jean Ritchie in The Dulcimer Book tells about visiting the MMA and seeing an instrument similar to her dulcimer and it was identified as a scheitholt. 8 We do not know if this is the same instrument. She also relates being in London and her husband spotting a book in a store window titled Stringed Instruments of the Middle Ages by Hortense Panum. 9 In the book Panum cites the Syntama Musicum and Praetorius’ description of the scheitholt. As far as we are able to determine, Ritchie is the first person to make the dulcimer/scheitholt connection.

Given the single source of the term scheitholt and the difference in construction from the instruments found in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina, and Ohio, we propose that we stop using the term. In its place we suggest that we call these American predecessors of the Appalachian mountain dulcimer Pennsylvania German zitters (zithers).

A problem with this proposal is that it assumes that they were first made in Pennsylvania either from memory of those instruments in Germany or from an actual instrument brought over during immigration. Copies of the Pennsylvania instrument were then made by craftsmen in the great valley of Virginia and western North Carolina.

Mercer documented a maker of these instruments in Berks County, Pennsylvania who was a Mennonite, but that may only be a reference to a maker of bowed zithers. 10 These instruments were constructed by craftsmen on an individual basis probably in home workshops. There is no record of musical instrument shops in the new world building these Pennsylvania German instruments.

Germans immigrated to North Carolina as early as the 1580s, but the greatest number came in the late 18th century. There is the possibility that these 11 immigrants were familiar with zitters and built them independently of the Pennsylvania tradition. However, Pennsylvania Dutch began migrating to western North Carolina in 1747. 12 This theory needs further exploration.

Ulrich lobbies for the name “Hummel,” which is descriptive of the droning sound of the instrument. He says, “In Germany, one notices with some amusement that in the USA today the old instruments of the settlers of previous centuries are always spoken and written about as German Scheitholt - even if they have many buzzing drones like the Hummel. After all it is important to recognize the origin of an instrument from a historical point of view.” 13 From a historical, geographical, and organological point of view there is no justification for calling the Pennsylvania German instruments scheitholts.

While we are open to using “Hummel” for these instruments, we feel there would be confusion with the European predecessors of the American made instruments. Since they tended to be made on an individual basis by hobbyists or in home workshops rather than by artisan guild members, we may never know the true story of the Pennsylvania German zitter. What we do know is that they are not scheitholts.

1 in Creuzburg (Thuringia, Germany) in 1571 and died in1621 (Wolfenbüttel, Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Germany). Praetorius was the premier Lutheran organist and hymn writer of 17th Century.

2 Syntagma Musicum, English translation p. 62 3 ibid. p. 62 4 ibid. p.62

5 Ulrich, Wilfried, English translation by Christa Farnon, The Story of the Hummel (German Scheitholt), p. 11

6 Mercer, Henry C., The Zithers of the Pennsylvania Germans, title page

7 Seeger, Charles, The Appalachian Dulcimer, p.43 7

8 Ritchie, Jean, The Dulcimer Book, p. 11

9 Ibid., p. 11

10 Mercer, p. 9

11 Baxley, Laura Young, German Settlers, The Encyclopedia of North Carolina, University of North Carolina Press, 2006. www.ncpedia.org

12 Ibid.

13 Ulrich, Wilfried, English translation by Christa Farnon, The Story of the Hummel (German Scheitholt), p. 21