I listened today, for the first time, by way of Kevin Teague’s 2025 YouTube video, to a Dulcimette - what Kevin describes as a backpacker dulcimer. Kevin's Dulcimette was built by James McAnulty. It’s tiny, and sounds pretty, if you like the higher pitched end of a dulcimer. Other players who’ve told me about this instrument have described it as if a mountain dulcimer met a ukulele and had a child. Will the idea take off? Hard to say. Is it now part of dulcimer history? Yes, for the moment anyway - depending on how it is cared about, played and cataloged. Kevin Teague has given it a fighting chance again, as it is not too common a sight.

What this miniaturized instrument type does, beyond what the luthier Ron Ewing desired back in 1975 when he created it, is to remind us that there will be no end to people tinkering with a good thing in an attempt to create something new and different. As an amateur luthier I say, “Great!” As a dulcimer player, I also say, “Great!” This being said (twice), the little Dulcimette also ends up being a big deal from the standpoint of why people who love a type of music and the instruments that create it go out of their way to understand the history and evolution of what is heard and played. Many find that by studying the old versions of the music, and even the old instruments themselves, we can play better and insure our modern instruments are not backsliding in workmanship and sound quality. There is merit to knowing the history – but the history of history can be deceptive.

Within the pages of many books, magazine articles and even pages and links on our DulcimerHistory.com site, lie the names of historical researchers and noted authors on the subject of the history of Mountain and Appalachian Dulcimers, and no doubt you’ll recognize many. Cecil Sharp from the 1920s, Charles Seeger (important article in 1958), Michael Murphy’s book in 1976, and L. Allen Smith’s book in 1983.

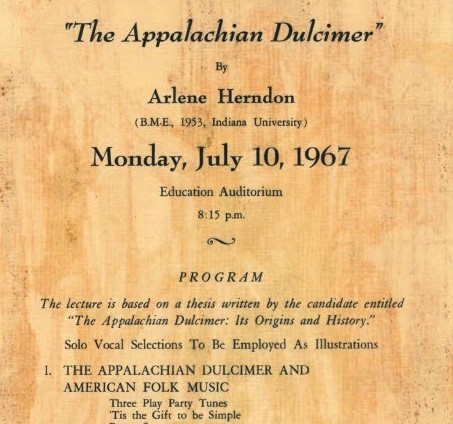

There is one researcher you may never have known of: Doris Arlene Herndon. Unlike those above listed, she loved to play the instrument. So much, in fact, that she made it her Master’s Thesis to the University of North Dakota in 1967.

In rubbing elbows with German instrument maker and researcher Wilfried Ulrich, I’ve learned an important lesson about history. He taught me that many musicologists and instrument historians often have had strong biases that could taint their research. In his book “Die Hummel” [The Story of the Hummel © 2011 – English version] he calls out some of these bold yet incorrect statements made by his historical predecessors, and repairs the damage done by them. The hummel is now called a hummel instead of something degrading, thanks to Ulrich’s take on history.

But can this still happen today in modern times? You Bet. Take, for instance, this quote: “Even though musicologist Charles Seeger (father of Pete) published an article in 1958 calling attention to the dulcimer as a legitimate subject for study, it is only since the early 1980s that scholars have been giving it serious consideration.” That quote is taken from a 2001 publication by University of North Carolina Professor Lucy Long. Professor Long has written some nice articles on the subject of mountain dulcimers in the early 2000s. However, Doris Arlene Herndon’s 1967 sixty page meisterwerk, as the Germans would say, should be considered a treasure on this subject! This is how history is sometimes mishandled. Here is a link to allow you to find and read Herndon’s original paper (a free download in .pdf available from her alma mater): https://commons.und.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5037&context=theses

As history buffs we must also allow some slack for those “in the know” prior to the internet, as they may never have known. Yes, this is said tongue-in-cheek, but it is also a warning that often the internet, even hyped up with AI juice, may not give one the correct answer either. I was told recently that the best dulcimer history list “ever” was at this link: https://www.bearmeadow.com/smi/krokbib.htm. While the list was extensive, it did not include many of the important scholarly publications that one might lean on today if dulcimer history was of the utmost importance.

Many dulcimer players find joy in playing, and within that group is a subset who finds joy in the history of the instrument and its culture as well. I once thought, “we few – we happy few,” but in the past few years more dulcimer history buffs are making their presence known. Good articles are showing up in Dulcimer Player News, some on line and many more thought filled and thoughtful than in the past – a sign that dulcimer players themselves are now doing more research and writing articles on the subject. There are many attics that still have not been cleaned out, and what will be discovered will add to the historical record. Our hope is that good information also continues to come to light - just like Mrs. Herndon’s paper. Thanks to diligent librarians and the digitization of past written records we, in 2026, are still in time to do good research, as non-AI-written work is likely the last stand for “real,” and will be hard to identify in the future.

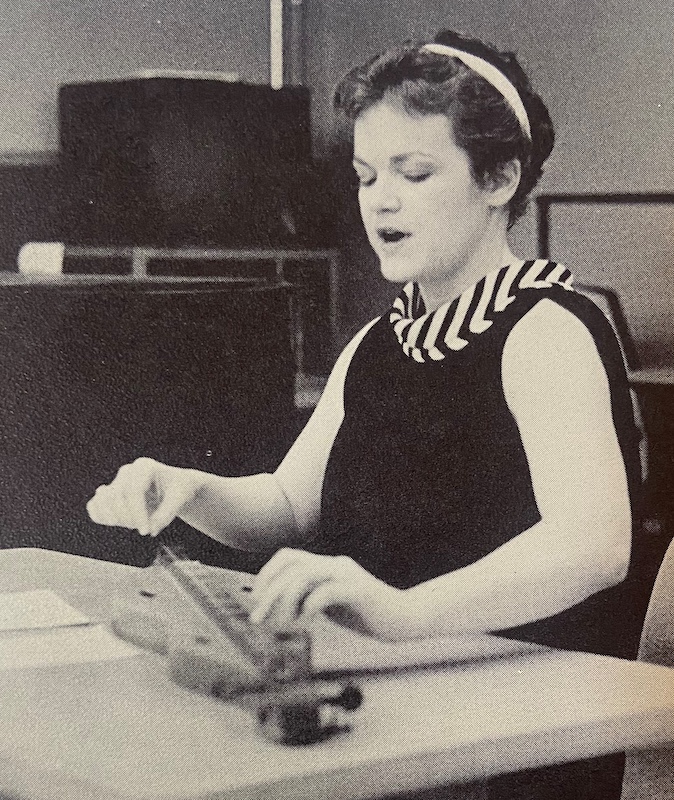

Sadly, Doris Arlene Herndon, a retired music teacher, passed away in 2020, so I could not talk to her about her paper and her passion. Her son, David Herndon, included the following in her eulogy and allows us to share it:

“My mom became interested in the old songs from the Southern Appalachians brought forward by Jean Ritchie. One of the instruments that Jean Ritchie used to accompany her singing was the Appalachian dulcimer. Quite intrigued by this instrument and the repertoire of songs associated with it, my mother enrolled in the music department at the University of North Dakota and wrote a master’s degree dissertation on the origin and history of the Appalachian dulcimer. This process culminated with a lecture and recital that took place in 1967.”

We also know she was awarded her Master’s Degree for her work on the origin and history of the mountain dulcimer. Her sense of the importance of the instrument was ahead of the Appalachian dulcimer revival-contemporary period in the 1970s when appreciation for the instrument swept the globe, thanks in part to the likes of John McCutcheon and Joni Mitchell. Her work in 1967 might not have brought her the notoriety of Cecil Sharp or Charles Seeger, but we know it brought her lasting joy and allowed us to better understand dulcimer history.