By Mark Dettmer

The history of Appalachian (mountain) dulcimers cannot be written without the mention of seclusion, remote isolation - and let’s face it - sometimes being an introvert.

The history of Appalachian (mountain) dulcimers cannot be written without the mention of seclusion, remote isolation - and let’s face it - sometimes being an introvert.

Scholars of the Hummel and early versions of the mountain dulcimer all point to these instruments’ uses in the teaching of music mainly for religious hymns and singing praise. No doubt, for many who owned the instrument in its early days, it was quiet, somewhat easy to learn, and personally portable, as it sat on one’s lap to played. Many of the first songs uncovered for the instrument’s ancestor, the monochord, are indeed personal and spiritual, and accompany drawings from 13th century monasteries illustrating just that. As the monochords evolved into the 15th and 16th century hummels (hummel is German for bumblebee) we understand that with the introduction of the simple drone stings that accompanied the melody string, the instrument had become a self-contained string band. The irony of the ballad style of song starting in the 15thcentury is not lost on music historians. More individuals were singing ballads than there were fine instruments in those days, and in rural and poor urban living areas the hummel was far more common than we realize.

While we might then imagine a lonely lad or a contemplative maid strumming solo away on a simple wood instrument in medieval days, there is little way to prove it until someone with extreme dulcimer credibility comes into the picture with sound reason and personal experience to how, likely throughout history, the mountain dulcimer was used by the group now known today as introverts.

It is because of Jean Ritchie that I can look my darling wife in the eyes and say, “No – I just cannot,” all the while owning three or four mountain dulcimers at any one time. The thought of playing in front of anyone leads me to not want to go near the instrument at all. So how did Jean Ritchie justify my dulcimer ownership and justify my happier solo alone time? She told us her father’s little secret…

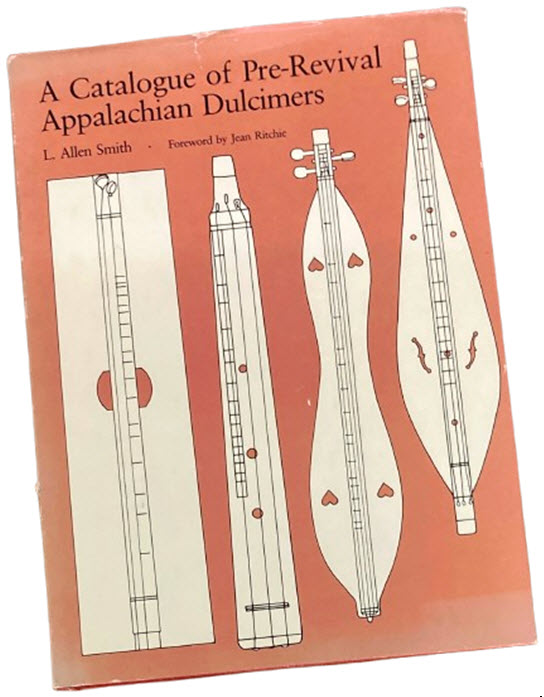

In the book, “A Catalog of Pre-revival Appalachian Dulcimers” by L. Allen Smith in 1983, Jean Ritchie educated the readers, by way of a forward to the book, as to why so few mountain dulcimers were discovered when the hunt was on in the 1920s by a number of research teams. To underscore her point, she told us the most personal and treasured dulcimer story we introverts could ever hear. For accuracy and the best understanding by all, including you extroverts, we will quote her directly:

“Let me speculate further, now, on the probable reasons the people did not bring dulcimers forward and offer to play them for the strangers from “over the waters.”

First, these folks felt a native modesty, shyness, an innate denial of having pleasure in one’s accomplishments not to do with making a living or with religion – the serious stuff of life. It is a mixture of these feelings that is one of the strongest ingredients in the very being of our people. Nowadays, of course, we have learned differently, but that trait has had to be educated out of us. I can illustrate only by remembering how it was in our family‘s younger days.

Back then, “the dulcimer” was spoken of in the same way as “the churn” or “the pickling-crock”. It was one of the household furnishings-things so ordinary as to go unnoticed until time came to use them. In our family, it was “Dad’s dulcimer,” and he did not play often, usually on a rainy day when he couldn’t go into the cornfield or perhaps at harvest time twilight when he would sit on the porch to rest and study the weather. We loved to hear his music, but we knew not to call attention to it, or praise him, for then he would lay the instrument down and nothing anyone said could get him to continue.

It was the same if someone came in and asked him to play. He would make excuses “Why, I can’t play; just knock around on it a little bit.” Or, “My hands a-gettin so stiff I can’t play to do any good. Never could anyway.” It seemed torture for him to play for an audience he knew to be listening. Occasionally one of us children would strum on the dulcimer, secretly, but it was considered Dad’s music, and so it was an unspoken understanding that none of us was to interfere. Other players around had the same ways with the dulcimer; they loved it but didn’t want to admit it meant anything to them and especially didn’t want to know anyone was listening.”

I can say personally that having read her words the first time, I felt as if I had a weight lifted off my shoulders. I guess it’s ironic that finding out one isn’t at all alone in wanting to be alone when they play is somewhat comforting. When I mentioned this to a couple of other players who knew I fixed dulcimers on the side, they admitted they did wonder if I played secretly or not. One said, “there are many music therapists who use the mountain dulcimer as a big part of their treatment and some of their patients will never be ‘cured’ until they read what Jean Ritchie revealed in her story.” Likely true.

Many mountain dulcimer players strive to play in traditional ways: noter, finger dancing, and such. I am content to now know that one of the true traditional and acceptable ways to play is also ‘alone’ - and without excuses. Funny how dulcimer history keeps teaching us things we already knew.